Stand and Face Me.

There was this one time when I was a kid–maybe twelve, fourteen, eight…

My mom took my sisters and I into Anthropologie (no I didn’t misspell the word, it’s a bougie, high-end clothing store that my mom loves and can only afford once a year because a dress is close to $150 and a fake fur jacket borders on 200-300).

Anyway, my sisters and I obviously weren’t going to buy anything, nor was my mother going to buy anything for us (except on our birthdays if we wanted one thing–a tradition I loved growing up but one that we no longer do…maybe it was never a tradition, though, maybe it only happened one year for my 13th birthday and that was that…though I think it was actually my 16th birthday, but I can’t remember because I have dissociative amnesia and my memory is more similar to bell-bottom jeans: super popular at one time, soon disappear, then slowly return in style); so, my sisters and I just strolled through the store, hiding in the clothing racks, smelling all the fancy candles in the beauty area, and scavenging through the sale section where all the actually ugly stuff gets put so you’re not really getting a good deal.

At some point I went off by myself to the home decor section. As I wandered around, seemingly aimless >but perhaps with a subconscious goal in mind< I discovered this big book of what looked to be a collection of photography. The cover was really beautiful and I liked the woman on the front who wore a very pretty white lace dress that made her look like a fairy. She had wavy dirty blonde hair, entangled with flowers of a variety. Maybe I was too young–I couldn’t tell if I wanted to be her, or if I simply wanted her.

Being the curious ‘’apt pupil‘’ I was, I thought, cleverly, “Well, it’s a book, might as well open it.” I turned the cover over and immediately my face went pink. Hesitating just a second before pounding it shut, I looked away, quickly scanning the store to make sure nobody saw me: eyes BULGING, heart p o u n d i n g, and sweat already seeping through my adolescent clothes.

As taught, I walked away, knowing I wasn’t supposed to look at the book. I pretended to distract myself with the peculiarly-fragranced candles–gin and lavender, lemon and parsnip, thyme and licorice, much more exotic than the B&BW birthday cake and candy-apple candles I was used to.

But, as Patrick Süskind says (I don’t really know anything about Patrick Süskin except that he’s a filmmaker),

Odors have a power of persuasion stronger than that of words, appearances, emotions, or will. The persuasive power of an odor cannot be fended off, it enters into us like breath into our lungs, it fills us up, imbues us totally. There is no remedy for it.*

Breathing in the lavender, the lemon, the licorice, an evocative heat churned within my lungs, unnamed, untamed. Once it had solidified in my gut, I felt my body moving back toward the sordid artifact resting deceptively innocent on the wooden table.

Tender, plush fingers slinked over the table a second time, traversing the rosy cover of the book. Stealthily, but with feigned restraint, I flipped the beautiful woman over and grazed a page of the book between shaking fingers. So scared, so worried of being caught, each time I turned a page a streak of warm sweat left its residue in the bottom corner.

Seeing that there was nobody near me at the moment, I took the chance to study the photographs more intently.

I couldn’t tell you the order, nor could I explain to you the theme or purpose of the book. All I remember is a few select pictures of the goddess-like woman posing nude in various positions within a field of sage-green grass and motley wildflowers. More importantly, though, I remember how it felt to lOOk at those photographs.

Never was there a more obedient, dutiful daughter or child than the one sneaking her way through forbidden pages (at least up until my family left our church and I was freed from the chains of eternal patriarchal subordination). But, unable to uphold my womanly duty at this moment, I let the waters of temptation engulf me, surrendering my eyes to this unknown woman’s lavish breasts and lucid skin, subtly colored with reddish-brown freckles and groves of hair in places completely foreign to ignorant eyes.

I thought she was beautiful. Each photograph revealed to the onlooker (in this case, me, a naive young girl) a new side to this elegant deity.

On one page she stood in front of the camera, frozen in the moment of her lifting the white lace dress over her head, her face covered, but hair pouring out from the gaps between her arms and shoulders. Nothing below her torso was visible in the frame, but in the somewhat blurry background I glimpsed a man funneling his gaze through an old-timey camera pointed toward the female specimen.

For some reason, glimpsing the intruder in the background made me upset. What was he doing taking photos of her without her knowing? Or, was she even aware that he was there, lurking like a leopard in the shadow of her silhouette? And if she did know, why was she turned toward me and not him?

Then, my heart speeding up, I wondered, Who was it taking her picture, then? Was it a man? Was it…another woman?

I pictured myself snapping a photograph of this stunning woman. Would my hands still be shaking, my fingers trembling over the capture button, making the photo blurry?

Then I envisioned myself in this same setting, but older. Suddenly, my hands no longer shook. They held steady to the camera, focusing it point-blank on the woman before me. Through the narrow lens I looked into her eyes. As she bent down to her knees, she looked back at me (but, in all honesty, she was really just looking at the camera) and smiled. I too dropped to my knees and moved a little closer.

As I adjusted the camera, I saw her begin to lift her dress up over her head, just like in the book. I knew I should look away, but I couldn’t. Then, again, my fingers started to quiver, my hands started to shake, and my heart sang out loud and clear within the dome of my ribcage.

Bare and beautiful, she smiled at me through the magnifying lense. Her lips gently vibrated as she whispered Shhhh, though I couldn’t hear a sound. Watching her press a sturdy finger to her mouth, I felt this woman slowly hushing all my anxieties. With the same hand she reached out to me, open-palmed. Wary, but unreluctant, I extended mine outward and felt it collapse into the folds of her sacred fingers.

I was still viewing her only through the camera lens, so I slowly set it down on the grass below my knees. But as I relinquished the camera to the ground, a wave of fear and guilt plummeted over me. What is wrong with me? I thought. And as a child would do, I threw my gaze toward the ground, avoiding the blatant image of the woman kneeling before me.

Looking downwards, as I adjusted the focal point of my own eyes, I caught sight of two small and round breasts clinging tightly to my chest. In a moment of recognition, realizing the bulbs belonged to me, I grew baffled…confused…repulsed.

My gaze continued down the trajectory of this new, strange body, and gradually my confusion and repulsion turned to amazement. A barren stomach, small and flat compared to the curvaceous one of the woman. I wondered if I could hold a child inside of it. I didn’t understand exactly how one brought a child about, other than by my belief that God bestowed it upon a young woman once she was married. But what if I didn’t want to be married?

I was quickly distracted by the dark shrub of hair poking out from between my thighs, thighs which were thicker than I remembered. Instinctively, I let my hand graze over the softness, brushing through it like one would a horse’s mane.

Suddenly, my movement was halted by the feeling of something wet. I’d felt a similar sensation before, but this time my fingers came up glistening. Moving them closer to my nose, I was reminded of the lemon-scented candle from the store.

That was when my awareness came back to life and a rush of panic instilled a thrum so violent in my chest and head that I thought I might faint. I looked down at my naked flesh and whispered, fearfully, What am I doing?!

Again came that consoling sound: Shhh…but now I actually heard it. Trying to locate the tune, I looked up and saw the radiating beauty of the woman before me, now mounted tall and strong like Praxiteles’s Aphrodite.

Stand, she said, and face me. This time I felt the crystalline voice flow through me as sharp and vehement as a river. As if carried upstream, I stood up.

Though her voice was brisk and piercing, the sight of her in the raw set the surrounding atmosphere ablaze. The closer I moved toward her, the wilder my skin burned. But when I suddenly felt the cool of her breast on mine, I thought the surrounding temperature had quite literally dropped below zero; but it wasn’t the kind of cool that somehow sucks the soul out of your body–it was the kind that nearly burns you to death as the lacerating wind slashes through the subliminal radiance of an auroral zone.

Then came the flash of lightning when I sensed the woman’s hand figure skating along my side. Slowly sculpting the now curvalent outline of my body, I felt a million lifetimes fly by as I stood there, frozen in the nuance of my own. I felt at odds with my body: on the outside, stiffened and cemented in place; on the inside, a seeping infestation of lava across the black folds of an erupting volcano. The woman pressed her hand to the naked skin protecting my heart. Shhh, she whispered.

And just like that, without a realizing consciousness of what I was doing, my lips glued themselves to hers like magnets. With the tender plush of her lips against mine (why do we say lips against each other? If anything, I think they melt into each other), the heat from within reconciled with the frozen solid of my exterior, and through me I felt lubricating my tissue and organs like a smooth honey, her soul falling into mine.

Brinn W.

* Patrick Süskind, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer.

All the Lives We Ever Loved

All the Lives We Ever Lived

The year is unimportant, the day irrelevant. The exact position of the second hand and the minute

hand and the hour hand of the bedside clock is unknown, for there are no clocks in this home…

*photo credits: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/100627372919934815/

Image credits: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/55591376645997060/

Preface

My hope with this story is to creatively illustrate some fragments I have extracted from reading Virginia Woolf’s novels, essays, and diaries, and place them in conversation with an author, poet, and female voice that was not only influenced by Woolf, but has greatly influenced me personally: Sylvia Plath.

I am currently conducting research on Plath–someone whose work (and life) shares many similarities with Woolf’s. Through my reading and extensive note-taking on Plath (as with Woolf), I have noticed Woolf’s presence all throughout the former’s work, specifically in her journals. I wanted, through this project, to challenge myself to think outside of my typical intellectual and creative paradigms. I feel that a short story is a great way to put two authors and their individual works in conversation. My overall goal was to create a kind of literary tapestry that interweaves various fragments from the lives and works of Woolf and Plath–something I hope to continue studying in my personal research.

Given that Woolf so often emphasized the importance of the “common mind” and the collective efforts of humanity, I think merging two authors that have had a significant impact on me and my work adheres to that same sentiment. In The Waves, Woolf writes from the character Bernard, “What I call ‘my life,’ it is not one life that I look back upon; I am not one person; I am many people.” I hope this story comes close to adequately epitomizing the collectivity of this project.

All the Lives We Ever Loved

The year is unimportant, the day irrelevant. The exact position of the second hand and the minute hand and the hour hand of the bedside clock is unknown, for there are no clocks in this home.

This is the kind of evening when one seems to be abroad: the window is open; the yellows & greys of the house seem exposed to the summer.

What I can tell you begins with the presence of two women, ageless, in a room of their own. They sit across from each other in front of a tall bay window, smudged with the fingerprints of seasons: the mud, the mist, the dawn. Its center glass pane is wide open, inviting a gentle, sun-filled breeze that brushes against the green walls, flutters the pages of novels along a tall bookshelf, and makes the floral curtains sway as to bachata.

“The first time I entered a psychiatrist’s office, I remember wondering why the room felt so safe.” This comes from the woman seated on the right. Her voice is round and full, spilling like a frothy white wave over the other woman, Virginia’s, body. She thinks the rawness in it is traced by something other than the shape and size of Sylvia’s vocal cords.

“Then I realized it was because there were no windows,” Sylvia says. Her tone indicates a mixture of sarcasm and seriousness.

“Ah, yes,” Virginia says as she returns her smile. “But is a window not better than some old ugly-patterned yellow wallpaper?”

“I should think so,” Sylvia admits. “Especially in that room. The walls were beige, and the carpets were beige, and the upholstered chairs and sofas were beige. And beige, I must say, is much worse than yellow.”

“I would have to agree. And there is something indescribably beautiful about windows. The way they bring in light, each day in a different configuration: miraculously. Frailly. In thin stripes. Hanging like a glass cage…a hoop to be fractured by a tiny jar. There is a spark there. Next moment a flush of dun. I think a nice, big window like this one lessens the barrier between the internal and external worlds–whether one looks out from their bedroom, or gazes up from the lawn.”

“Yes, that is very true,” Sylvia replies. “I have always felt that gaping out my window somehow alters my sense of space. There is, of course, a physical boundary between us and the outside world, but, as you say, that boundary is diminished–in part, I think, by its transparency.”

“Space, yes,” Virginia agrees. “And also time. With my cheek leant upon the window pane I like to fancy that I am pressing as closely as can be upon the massy wall of time, which is forever lifting and pulling and letting fresh spaces of life in upon us. In these moments I find myself overwhelmed by a voice of desire crying, may it be mine to taste the moment before it has spread itself over the rest of the world!”

Sylvia smiles in understanding. “Many days have I spent gazing out my bedroom window pondering just the same thing. Hell, I still do this! I feel I live every moment with terrible intensity. Staring out into the sky’s stagnant blue I whisper to myself,” (her voice lowers and softens), “Remember, remember, this is now, and now, and now. Live it, feel it, cling to it.” Her tone suggests she is still, at this moment, trying to incentivize herself.

“Yes, because even in the faceless blue of the sky,” Virginia adds, “we glimpse the very essence of Life! Floating solemnly in the air, like invisible wisps of hay, of hair, of clouds. And I want to see and feel every single one of them.”

“I want to become acutely aware of all I’ve taken for granted,” Sylvia continues. “All those fleeting fragments–that essence of living, of simply being alive, of sensing the iambic heart in one’s chest, singing, ‘I am, I am, I am.’ That is the voice for me.”

Virginia nods. “This is the secret of happiness, I feel.” She pauses before adding, “But I don’t think of the future, or the past, I feast on the moment.”

“Oh yes,” Sylvia chimes, “I agree. With me, the present is forever and forever is always shifting, flowing, melting. This second is life. And when it is gone it is dead.”

“In a world which contains the present moment,” Virginia adds, “why discriminate? Nothing should be named lest by doing so we change it. Let it exist–whatever it is–this beauty,” (she gestures out the window, then toward her friend), “and I, for one instant, steeped in pleasure.”

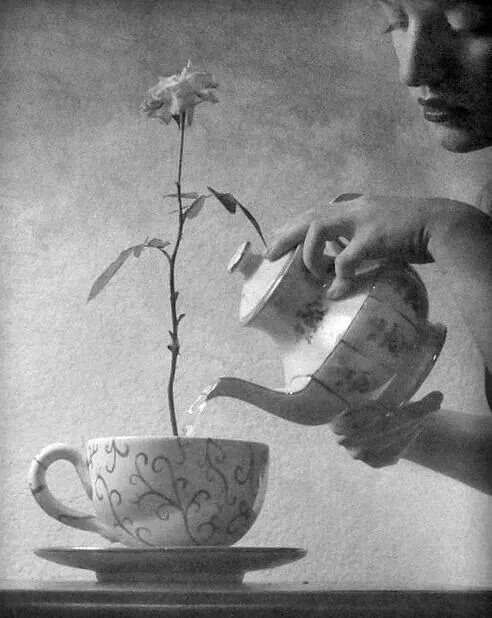

Sensing the amplitude of each other’s presence, they are warmed by an air of mutual understanding. “Speaking of being steeped in pleasure,” Sylvia signals with her open hand to the tea table in the corner of the room, “would you like any?”

“Oh, that would be lovely, thank you, Syl.”

Sylvia makes her way to the tea tray. As she gets up, she glances out the window and catches sight of the lustrous garden below. She is reminded of the many summer days she spent setting strawberry runners in the sun. Her lips mold into a soft, effortless smile and she sighs a nostalgic breath.

“Oh, Jinny,” Sylvia adds, looking down at the tray. “I forgot we also have fresh orange juice and steaming café au lait, if you’d prefer that instead?”

Virginia flaps her hand lightly in refusal. “Tea is just fine for me.”

Sylvia lifts the silver teapot with her right hand and pours the steaming, aromatic liquid into two white teacups with blue detailing. Though they appear to be the same cup, they are in fact not: one holds the small outline of what looks to be a cat, though the absence of a tail makes her second guess. The creature’s legs are painted along the bottom of the brittle china, giving the impression that it is headed somewhere. The other teacup is marked by the small but sturdy shape of a horse: riderless, a free thing, God’s lioness. The memory of her horse-riding days gallops into Sylvia’s awareness. She feels, for a moment, that she is back in Devon: between her thighs a bare brown back, the gentle, motherly stroke of her hand along The brown arc of the neck. She, Lady Godiva. An all-consuming yearning to return there creeps into her being.

Sylvia hands Virginia her tea. As the latter lifts the cup to her thin lips, she too takes notice of the blue cat that lengthens its limbs across china. “A queer animal, quaint rather than beautiful,” she notes.

Sylvia retreats to the tea table once again and wheels it over to the windowsill. Virginia sets her cup down, not without first letting its heat spread to her hands. The light breeze has, for some unknown reason, initiated an outburst of shivers across her skin. Sylvia notices this and asks, “Would you like me to shut the window?”

“No, that’s alright,” Virginia replies. “Thank you, though. It seems the older I get the more sensitive I become to the wind.” The breath of the wind is like a tiger panting, she imagines.

Sylvia sits down again. “Now, where were we?”

“The present moment, I believe.” The women laugh. “Ah, but how to focus on the present with the insatiable desire to write something before I die, this ravaging sense of the shortness & feverishness of life, making me cling, like a man on a rock, to my one anchor?” Virginia is exasperated but equanimous.

“And what is that anchor?”

“Writing, I suppose.” Sylvia nods in understanding.

Then Virginia turns the question over to her friend. “At present, have you been writing anything that you’re particularly enjoying?”

Sylvia sighs. She enjoys the process of writing, but when it comes to prose, the task seems to be much more difficult. She had written hundreds of poems, but prose never came to her as easily. “For me, poetry is an evasion from the real job of writing prose” she admits to her friend.

“Well,” Virginia replies, “we cannot command all our faculties and keep our reason and our judgment nor memory at attention while chapter swings on top of chapter. Writing prose is a kind of lifestyle, I think.” Sylvia nods in agreement, feeling a sense of ease wash over her, for she knows she is not alone in this struggle. “Especially,” Virginia continues, “in a state of illness, which I am sure you empathize with.” Sylvia's head bobs quickly up and down.

“Nevertheless,” Virginia adds, humbly, “still it would be easier to write prose and fiction there than to write poetry or a play. Less concentration is required.” Virginia senses her friend’s mind traveling to some near yet distant past she has had no presence in, no influence on.

The latter sits with Virginia’s take for a moment. Then she replies, “Sure, yes–less concentration, perhaps. But I always was interested in prose. As a teenager, I published short stories. And I always wanted to write the long short story, I wanted to write a novel. Now that I have attained, shall I say, a respectable age, and have had experiences, I feel much more interested in prose, in the novel.”

Virginia smiles. She knows precisely how she wants to respond, but she waits, allowing her friend to continue her curious thought.

Sylvia adjusts her position, unfolding her hands so they both lay open on her thighs. “I feel that in a novel, for example, you can get in toothbrushes and all the paraphernalia that one finds in daily life, and I find this more difficult in poetry. Does that make sense?”

“Definitely it does,” Virginia assures her. “In different words, the poet gives us his essence, but prose takes the mold of the body and mind. It’s a different kind of art, with a different purpose.”

“Exactly.”

They sit, for a moment, in silent unison. Both pairs of eyes stray out the bay window. Virginia catches sight of the death-woven violets resting peacefully below green boughs and flowering branches.

Sylvia is drawn to lines of sundry roses that color the bright green lawn. She feels a sense of gratitude fold over her mind as she ponders the bulging bulbs below. “A little thing,” she thinks, “like children putting flowers in my hair, can fill up the widening cracks in my self-assurance like soothing lanolin.”

“That reminds me,” Sylvia says to her friend, “of one year when I worked for this magazine. At the end of the summer internship, the directors had all the girls in the program pose for photographs. They asked each of us to hold some sort of object that encapsulated our individual ‘essence,’ based on what we wanted to do for a career. When they asked me what I wanted to be I said I didn’t know. I want to be everything.

“They said I had to choose something, so I said a poet. But I mean, how do you represent a poet with a single object?”

“I couldn’t tell you,” Virginia laughs. “The whole world?”

“Well, I ended up with a single, long-stemmed paper rose.”

“Hmm,” Virginia ponders. “Well, I’ve always thought that until we can comprehend the beguiling beauty of a single flower, we are woefully unable to grasp the meaning and potential of life itself. And since that is, in a way, the poet’s desire…”

Sylvia considers. “I guess you are right.” Pausing for a moment, then she continues, “Later, after the photoshoot, I took the rose back home and fitted it neatly under a glass case that was gifted to my mother, by her mother, many years ago, before I was born. For years the jar had been sitting in our living room–untouched, useless.

“I thought, after placing the rose upright within the transparent enclosure, how this inanimate object was precisely what everyone was expecting me to be: a fragile paper rose, never growing, never dying, standing tall and glamorous for all the visitors of our home to see. It was odd too, given that growing up, our home was like a plant nursery: its steamy windows, round tables facing rough glass windows bordered by green potted plants. I guess we stopped buying and growing them after my father died.”

As Sylvia recounts her anecdote, Virginia smiles with care and understanding, for she too has been faced with death from a young age.

She allows the former’s words to sink in before she replies, thoughtfully, “Ah, but how frightening it might have been (and may still be!) to those visitors, and even to one’s own self, when a petal drops from the rose in the jar…”

“Yes!” Sylvia exclaims. “For little did they know that perched humbly behind that real flower was a phantom flower, seemingly invisible, but there.”

“Yet,” Virginia adds to Sylvia’s words, “the phantom was part of the flower for when a bud broke free, the paler flower in the glass opened a bud too.”

Virginia watches as the glow in her friend’s expression rises to the round surface of her face. It is as if the whites of her eyes have been filled with the sun’s rays, emitting light like a star.

Meanwhile, Sylvia thinks, “To learn and think; to think and live; to live and learn; this always, with new insight, new understanding, and new love. How lucky am I to experience this with my dear friend.” Then, speaking to Virginia, she says, “Most people see such a thing and believe it to be nothing more than a dream–and a nightmarish one at that. But how to exactly decipher between a dream and a nightmare? And then what about reality?”

“Absolutely,” Virginia replies. “Behind the cotton wool of ‘reality,’ is hidden a pattern; that we–I mean all human beings–are connected with. Some people just don’t sense it.”

The other nods in agreement. Again she is reminded of a distant memory, something her mother once said to her as they were driving home from the hospital. Keeping her eyes on the road, she muttered, almost under her breath, “Sylvia, let us act as if all this were a bad dream.”

Looking to Virginia, Sylvia says, “To the person in the bell jar–real or phantom–the world itself is the bad dream.”

“Suppose the looking glass smashes, the image disappears, and the romantic figure with the green of forest depths all about it is there no longer, but only that shell of a person which is seen by other people - what an airless, shallow, bald, prominent world it becomes! Yet how glorious when we break free from the borders of that glass house,” Virginia smiles.

Sylvia nods and smiles also. She remembers being trapped inside those hedges, questioning every facet of her existence, the purpose of her living, constantly revisiting the impression that “everything people did seemed so silly, because they only died in the end.” The thought, though it still holds a level of truth, seems largely unimportant at the present moment.

As if the other can sense her friend’s brooding, Virginia becomes evocatively aware of the overwhelming presence of Time. “Time seems endless, ambition vain,” she thinks. “Over all broods a sense of the uselessness of human exertion.” But another voice rings out in her head–one that is louder, more potent.

“There can be no doubt,” she says aloud, “that our mean lives, unsightly as they are, put on splendour and have meaning only under the eyes of love. Wouldn’t you agree?”

“Absolutely,” Sylvia confirms. “And not just romantic love. I mean, I love people. Everybody. I love them, I think, as a stamp collector loves his collection. Every story, every incident, every bit of conversation is raw material for me.”

“Then we are both stamp collectors, with a great deal of beloved stamps.” The women share light laughter. “Stamps of all shapes and sizes, I might add.”

“From every corner of the world,” Sylvia continues. “And how I love them all. I would like to be everyone, a cripple, a dying man, a whore.” She pauses, witnessing, as if from an exterior perspective, the montage of images that have sequenced sporadically in her head. “I guess, perhaps, this is one of the many gifts of being a writer. To occupy another’s black patent leather shoes for an afternoon, a day, a week–and then come back to write about my thoughts, my emotions, as that person.”

“Indeed. The writer is one of many lives, many faces; yet somehow also faceless. We are not as simple as our friends would have us to meet their needs.” Virginia pauses for a moment. “Yet love is simple.”

“Ah, yes,” Sylvia replies. “And if I have learned nothing else, it is to listen and to love: everyone.” She gestures to her friend. “I love you because you are me, in a way–my writing, my desire to be many lives.”

“And mine also,” Virginia replies, kindly. “I have lived a thousand lives already, it seems. But in this life, it is here that we are drawn into this communion by some deep, some common emotion. Shall we call it, conveniently, ‘love’?”

“I don’t know. I think the word is often overused, misused. Love–the four-letter word with far more meanings than we can even begin to understand. But I think we glimpse it authentically here and there, or feel it melting over us in certain moments that seem…extraordinary.”

“This being one of them,” Virginia notes, smiling.

Sylvia smiles also. They sit in silence for a moment, content in one another’s presence. Then Sylvia sighs. “How we need another soul to cling to.”

“We do not know our own souls, let alone the souls of others,” Virginia notes. “But I think it is in the process of connecting with another that we not only come to know them better, but ourselves.”

Sylvia nods. “Human connection is as essential to life as the air we breathe, I believe. So many people are shut up tight inside themselves like boxes, yet they would open up, unfolding quite wonderfully, if only you were interested in them.” She pauses before adding, “I am glad I have found someone with whom I can unfold the great corollas of my Self.”

“And I also,” Virginia replies warmly. “Some people go to priests; others to poetry; I to my friends, I to my own heart, which beats in unison with yours. I feel it–in this very moment.”

An intimacy is shared between the two women. How it is transmuted is unclear: through eye contact, their particular exchange of words, the shared aroma of tea…who’s to say?

A great deal has been said, been shared, but the most is conveyed in this singular moment: enmeshed in the invisible string that runs between these two sets of eyes, these two fugacious bodies, linking them together indefinitely.

At last Virginia says, “The sun is sinking,”

“Perhaps we should head home,” Sylvia replies.

They nod and stand up. After returning their teacups to the tea tray, they gently close the window and depart.

Out in the open air of the world, it appears the brilliant amorous day was divided as sheerly from the night as land from water. People of all shapes and sizes walk the darkening streets. Of our crepuscular half-lights and lingering twilights they know nothing. And in voices that can only be distinguished by the dead, the poets sing beautifully how roses fade and petals fall.

The two women stride, side by side, down the lamp-lit streets of some city, some neighborhood that is, at this moment, nonexistent. Despite the cold air that has taken hold of such a lovely, radiant day, each woman smiles to herself as that feeling, which cannot be labeled with words, unfurls over her mind and body, steeping itself deeply into her soul.

One woman thinks to herself, “I may never be happy, but tonight I am content.” The other, in the same blip of acute awareness, says to herself, “I have had one moment of enormous peace. This perhaps is happiness.”

Just as both wisps of thought begin to fade, mixing into the ever-growing, ethereal black sky, Virginia and Sylvia find themselves each arriving at their destination.

Inside, one observes the yellow-wallpapered room glowing subtly in the unraveling twilight; and from the outside, the window slowly slowly coming alive in a chiaroscuro of shadows and stars. Below the enormous bay window, an elm tree with freshly greening leaves dances in the wind. Next to it, a weeping pagoda kneels humbly toward the ground. The trees are separated by two gravestones, beneath which their roots intertwine.

There I stand, and if I listen closely I can hear a quiet refrain echoing in the breeze:

all the lives we ever lived and all the lives to be

are full of trees and changing leaves.

I am Home.

e e cummings, landscape in blue, Oil On Canvas, 12" x 10", not dated.

Works Cited

Gilman, Charlotte Perkins. “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Virago Press, 1981.

Orr, Peter. Interview with Sylvia Plath, The Spoken Word, 1962, https://youtu.be/fAss2OpuUiE?si=qwsDV-scOqbnXLdj.

Plath, Sylvia. “Ariel,” Ariel, Faber & Faber, 1965.

Plath, Sylvia. “The Beekeeper’s Daughter,” The Colossus and Other Poems, Vintage International Ed., 1998.

Plath, Sylvia. The Bell Jar, Faber & Faber, 2005.

Plath, Sylvia. “Initiation,” Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams, Faber and Faber, 1977.

Plath, Sylvia. The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath, First Anchor Books, 2000.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own, Penguin Books, 2004.

Woolf, Virginia. “A Sketch of the Past,” Moments of Being. Ed. Jeanne Schulkind. 2nd ed. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1985, pp. 72.

Woolf, Virginia. “On Being Ill,” London: Hogarth Press, 1930.

Woolf, Virginia. The Captain’s Death Bed and Other Essays, London: Hogarth Press, 1950.

Woolf, Virginia. The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Volume 3: 1925–1930. Ed. Anne Olivier Bell. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980, pp. 36.

Woolf, Virginia. “The Journal of Mistress Joan Martyn,” 1906.

Woolf, Virginia. The Waves, Mariner Books Classics, 1950.

Written by Brinn Wallin for UCLA class, “Virginia Woolf,” Professor Louise Hornby, Final Creative Project

This short story was created and written by Brinn Wallin. Please do not steal or copy without permission.

*All Rights Reserved*Orange

Orange

Image credits: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/23081016835555521/

“My God, a moment of bliss. Why, isn’t that enough for a whole lifetime?”

July. What color would July be if one could see it painted on a blank and meager wall? Not red, not yellow, nor any darker hue. Orange. Orange would be the color of July. Orange, like the fruit when it ripens in the winter, glowing heavily in the pockets of a young boy, empowering him to embrace his first love. Orange, like a California poppy scuffed by dirt and roughed by a brazened summer sun, blossoming poisonously in the mouths of rejected sons and daughters. Orange, like a dimly-lit jazz club in Paris, buzzing with eager, tipsy, and lustful youth.

There, within the walls of that dungeon-like bar situated in the heart of Paris, a young woman stood inside dressed in sparkling black. Her long, blonde hair was gathered behind her head with a pale blue ribbon slightly brighter than the color of her eyes. Pearls rested on her neck, glistening against the white of her collarbone. And everywhere around her beamed a dangerous orange glow. Dangerous, like a juvenile inferno gaining multitude and magnitude with every breath of oxygen feeding it. Dangerous, because once a fire is started, it’s hard to let go. She thought she’d light a match, kindle it a little, watch it as a bright yellow flame erupted from a single strike, hoping that this sole flame would be enough.

But as the night sweltered on, this orange madness only grew and grew, taller and wider until every corner of the bar reflected potent flames back into her eyes. Not even a pair of oceanic-blue eyes could water down the magma spreading throughout her chest, the lava bubbling across her hands and legs, the heat beating almost sonically between her thighs. By the time the club was closed–the medieval wooden doors firmly shut, the vivid red lights illuminating the lettering along the outside walls dimmed completely–she felt her heart drop. She watched and silently mourned as the fire slowly disintegrated between her and this stranger she’d only just met. Even the thought of goodbye aroused tears in her eyes–tears that would surely kill this fire completely.

As their hands unlinked and fell each to their sides, she forced her eyes to stay put on his, even though she could feel the waterfall inside her about to overflow. Please don’t go. Please tell me you can stay. Please don’t walk away and leave her alone, she begged him inside her head. Though she was not alone but accompanied by two friends and a school of drunk men and women dancing rowdily inside a reggae club just across the street, she knew the moment they parted it would seem as though nobody else existed in the room but herself. This was exactly how it felt being with him–as though nobody but the two of them occupied the space, the world around them, with only an electric wave of bliss radiating between them.

But that sweet, fiery bliss had evaporated into the thick and musty air of the Paris streets at two a.m., nowhere to be found now that they had woken from their dream of heavy orange light, distant jazz music, and love at first conversation and touch.

I’ll see you tomorrow, he had whispered softly, sweetly, with honest intent behind every word. She knew it was not possible though, that this was it. This night could not go on forever. What seemed like a single moment of bliss was actually hours upon hours of time passing, and it would die as quickly as it had been born. Her only hope was that some new and foreign phoenix would rise from the ashes of their dissipated moment, capture her in its arms, and steal her away to another dimension of love’s euphoria. It was only a matter of when.

Still she begged, Don’t go. We can hold on to this night, make it last until the morning’s evil sunrise renders no choice but to leave it all behind. But her internal pleas were useless. He could not read her mind, nor could he obey her requests. And she knew this.

She watched with melancholic eyes as every speck of dust wafted into the conglomerate shadow of a million dying stars and faded silhouettes—lifetimes forever illumined by one night in July’s orange glow.

Written By Brinn Wallin

Published in Precipice Magazine, “Overture - Issue 1,” Winter 2025, https://www.precipicemag.org/issue-1/orange-brinn-wallin

This poem was created and written by Brinn Wallin. Please do not steal or copy without permission.

*All Rights Reserved*Robin

Robin

Image credits: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/11540542789718225/

In the gray mist that clouds the early morning sky just before the sun starts to rise, a young woman crouches in front of her glass bedroom door and notices a chubby little bird huddled on the cold concrete next to a planter box. He (for she assumes the little animal is a he) appears to be perfectly calm and cozy; but when she looks more closely, she perceives a bout of miniscule tremors causing his plump body to shake. The sullen sky suggests a forecast of rain, so maybe he is only shivering from the cold, she thinks. As she watches him, knowing something is off but not able to tell what it is exactly, she feels that he can sense her presence, her round and intimidating eyes staring straight at him through the glass door that separates them by only a few feet. She wishes she could look more deeply into his eyes, but they are so tiny, almost microscopic, and so brown they look black.

Birds have feathers, of course; but this little one looks like he is wearing a big fur coat, slightly ruffled and dirty from…a long journey? She wonders where he has come from; perhaps some unknown land that is vastly different from the boring streets of the college town he has found himself stranded in. However, as she studies his tattered and worn jacket, she realizes that his feathers are only giving the impression of a puffy mink-colored parka because his right wing is all maimed and broken.

This sudden realization brings with it a chilling wave of sadness. Immediately, as the little bird shuffles around, revealing the scruffy, futile lump of gray and white feathers that coat the right side of his body, the woman’s mind shifts into panic-mode: What to do? How to help him? Who hurt this little baby? She tries to conjure up some solution to the earth-shattering crisis before her; thinking up some way to save this poor creature who is so innocent, so naive, in his unequivocal suffering. But she can think of nothing. Even if she could, though, she is already running late for work–which starts in half an hour and takes twenty minutes to walk to, and she is still in her pajamas.

But she sits there with the battered bird until she sees him start to hop away, a bit frantically, given that he is likely also surprised by his inability to fly–a skill he never understood as a skill, since it always came naturally to him. She thinks to herself, my little bird friend knows that to be a bird means to be resilient. And in unison with the thought, the little robin discovers a rhythm in his skinny legs that allows him to hop away and mount the tall steps that connect the woman’s patio to the sidewalk adjacent to the busy street. Up those steps and to the right and left there are plenty of nooks and crannies where the bird can find shelter while he meditates on what to do next. Because, again, she thinks, if my little friend contains any knowledge within that spec of matter inside his head, it is knowledge on how to bounce back (quite literally).

She follows the robin outside to ensure that he is safe and sound, but when she too mounts the steps, she grows slightly worried, as she cannot find him anywhere. She waits for a moment, just to be sure he won’t jump out from behind a bush, beckoning to her that he desperately needs her help. When she sees no sign of him, his puffy parka, or his scraggly legs, she makes her way back inside and proceeds to get ready for work.

She is now an hour into her shift, which she has spent sitting at her desk, ruminating on the bittersweet encounter she had today. The day prior, she almost took her life–one of several almost-attempts in the last few months. Immersed waist-high in the ocean, rocks of many shapes and sizes sagging in her trench coat pockets, she found herself being held back, her bare feet locked into the wet sand caked beneath the cold and murky water. Then it had started to rain. She loved the rain, but she had hoped that when she waded into the vast sea, she would be consumed solely by the water below. She wanted the air to be fresh and crisp and clear, so she could truly relish in her last breath. And she imagined being able to open her eyes to the sky and look directly into the sun, not caring if it blinded her, for it wouldn’t matter.

But here she was, breathing in the not-so-fresh air of her office, the waters of yesterday drained completely from her mind. Her only thoughts were of her little bird friend.

This seemingly inconsequential event cuts deeper than any razor or any knife she’d ever used before. As she repaints the image of the baby robin outside her glass door, she is reminded of a favorite poem–one she has visually depicted on the skin of her right arm:

“Hope” is the thing with feathers -

That perches in the soul -

And sings the tune without the words -

And never stops - at all -

And sweetest - in the Gale - is heard -

And sore must be the storm -

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm -

I’ve heard it in the chillest land -

And on the strangest Sea -

Yet - never - in Extremity,

It asked a crumb - of me.

Strangely enough, earlier in the day prior, as the young woman was walking home from class to her apartment, preparing for her trip later that evening to the beach, she crossed paths with an old friend she hadn't seen in years. They exchanged brief and insubstantial small talk, before her friend made a sudden comment about the weather:

“I really would love it if it started raining,” he said.

The young woman gave him an amused look and replied, “Really? I’ve been banking on the sun coming out all day. It’s there, hiding behind the clouds, teasing us. I hope I can will it to come out somehow.”

They shared some light laughter and then the friend replied, “Well, I’m hopeful for you.”

The comment really didn’t mean much to him, but to her, it consumed her whole being. She did not know why exactly, for the phrase was nothing special, really. They said their goodbyes and parted ways, and the four-letter word lingered in the young woman’s mind all the way home.

Now, sitting in her office, the word returns to her consciousness, entwined with the memory of her little bird friend. She senses an unanticipated feeling of warmth and comfort rush over her body like a wave. She thinks to herself, Though my right wing may also be somewhat dismembered and broken right now, I am, down to my core, immensely resilient. If a little helpless creature like my robin friend–with his grain-sized brain and shabby feathers, his twigs of legs and black holes of eyes–if he can hop away and find protection for himself, even if it doesn’t prevent his eventual dying, I too can find a way to ‘hop’ forward, to keep on keeping on.

Whether he knows it or not, my little feathered friend perched himself within my soul today and instilled within my beating heart a flutter of hope. I hear his tune; and just as I could never turn and look the other way from a small and sweet little bird huddled outside my glass door, I also cannot ignore the small and sweet little girl huddled within me, begging that I listen to that hopeful tune.

Written by Brinn Wallin

This poem was created and written by Brinn Wallin. Please do not steal or copy without permission. *All Rights Reserved*